Mia: “Ahead of Her Time”, an essay by Ashley Plant

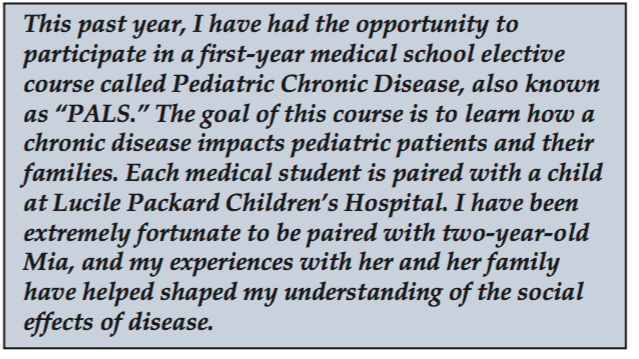

Mia was ahead of her time from the very moment she arrived. She was born at 36 weeks gestation but grew into a rambunctious infant radiating the adorable smiles only babies can give, those that give you a sudden urge to pinch those round bouncy cheeks. She attained the appropriate percentiles on body mass index charts at the pediatrician’s of ce, hit every developmental milestone, and continued to be a source of absolute joy to her parents and spunky three-year-old brother. Her life was that of a normal baby, with her parents cherishing every moment of innocence and beauty and looking ahead to her having an unhin- dered future that would doubtless change the world.

Like the unexpected crash of a wave out of rhythm, the four-month mark heralded a great change for Mia and her family—the beginning of Mia’s body’s rebellion. She began to vomit after breastfeeding, stopped gaining weight, and seemed to reach a wall in development. Anna and Mathai Mammen, Mia’s adoring parents, took her to the Gastroenterology clinic at Packard Children’s Hospital, where blood tests revealed that Mia was severely anemic and prompted Mia’s immediate admittal for treatment and diagnosis.

Tests, procedures, consults, and intensely stressful situations consumed the greater part of the next ten days. Anna and Mathai had expected that watching Mia undergo multiple uncomfortable and painful procedures would be dif cult, but their stress was compounded by Mia’s “failure to thrive” diagnosis, which required that the hospital staff first rule out parental neglect or ignorance. Despite a warning from Mathai, a physician himself, Anna was unprepared for the attention focused on her, ranging from her breastfeeding technique to the quantity and quality of breastmilk produced.

Mia’s dangerously low hematocrit was corrected, but she was discharged without a diagnosis. Although she probably had a metabolic disorder given the constellation of her symptoms, the speci c disorder eluded identi cation. Such began the trial-and-error phase of her care. To improve her weight gain, Mia was discharged with a nasogastric tube and supplemented with formula; however, even the most elemental of formulas caused acute liver failure. Anna and Mathai undertook the task of researching the components of these formulas and made a number of suggestions to the medical teams, but ultimately, Mia could only tolerate Anna’s breast milk, but her mother had to follow a very strict diet. Anna once described this diet to me as “dry, boring chicken breasts… and that’s it.” This solution seemed to work, and Anna embarked on what would end up being two years of breast-feeding and chicken breast-dieting with no diagnosis or respite in sight. They even invested in breast milk from a bank, but that, too, resulted in Mia’s suffering. There were many days when Mia would cry for 20 hours straight, sleeping for only one minute at a time. Mia’s body was frozen in time with no substantial growth and a slow, progressive loss of important developmental milestones. It doesn’t seem to cross our minds that baby steps may not culminate in running and playing for some children like Mia, whose rst baby steps were her only ones.

Anna became weak and malnourished herself with two years of breast-feeding on a highly restricted diet. Mentally, she and Mathai had reached their nadir. Mia’s brother, Mathew, was also feeling the effects of a family in crisis. Mathew had almost been kicked out of Chinese school for acting out in class, and he once threw a tantrum during one of Mia’s many hospitalizations, culminating in his storming out of the room. It is hard for a six-year- old who is as active and intelligent as Mathew to have the patience to deal with his sister’s disease. When I had lunch with the Mammens, Mathew jabbered nonstop about soccer, kindergarten, and his new video game and was disappointed when his parents explained to him that I couldn’t play because we were talking about Mia. I’m not sure what Mathew must think about this whole situation, but he is as affected by Mia’s disease as anyone else.

Mia’s health also continued to suffer despite Anna’s best efforts at providing nutrition through her breast milk; her hair was turning white and showing other signs of protein de ciency. Breastfeeding was neither sustainable for Anna nor suf cient for Mia, and total parenteral nutrition (TPN), an intravenous food source, represented a shot-in-the-dark hope to keep Mia fed. However, this option was not without its risks. Although Anna’s physical health required that she stop breast-feeding, should TPN not work, Anna’s milk source would be gone and there would be no alternatives to feeding Mia. Given her mysterious intoler- ance of elemental formulas, her risk of intolerance was even greater. It came time to think about issues no parent ever wants to think about, let alone set up legal documen- tation to address. Although Mia’s parents have been emotionally taxed with physicians insinuating neglect or gross incompetence on their part, signing a Do Not Resuscitate order for their two-and-half-year-old daughter forced them to confront issues of life that many individuals have never faced. Anna and Mathai had to accept that the physicians were no closer to a diagnosis of this charted “unknown metabolic disease” and that Mia had deteriorated signi – cantly. A recent MRI showed shrinkage and a mysterious deposition of mineral throughout Mia’s brain. The image showed a clear deterioration from the rst MRI when she was initially admitted. The once vibrant child now ap- peared with partial vision, mixed tone in her muscles, an enlarged liver, loss of most of her muscle function, and,

the worst symptom of all, extreme pain. From a few steps and a crawl, Mia had regressed to being unable to hold her head up again. Anna and Mathai faced these challenges head on, agreeing that the most important goal was to increase her quality of life. With crossed ngers and many prayers, Mia was put on TPN. Thankfully, it was successful. It seemed that if Mia’s digestive system could be avoided all together, some of the mutiny inside her could be bypassed.

But after many hospitalizations, bitter realizations of their daughter’s dire situation, and placing their lives on hold, Mia’s parents took her home and started her palliative care. She was given oxycodone, valium, steroids, and anti-seizure medications and referred to see a gastroente ologist, a neurologist, a developmental biologist, and an endocrinologist regularly. During this lull in the tidal wave of Mia’s disease, Anna and her husband finally re-experienced one of the small pleasures of life—going out to dinner, their first opportunity in over two years.

It was during this calm that I went on an appointment with Mia. Anna was surprisingly joyful because she was excited to share with the physician that not only had she gone out to dinner, but she had also eaten what she wanted and had two glasses of wine. Chicken breast dieting and two years of breast-feeding made those two glasses of wine the most appreciated and desired glasses of wine in the world. Yet despite this transient pleasure, there was still the fear of what Mia’s future would hold.

I went to the Mammen home to see what daily life with Mia was like. Palliative care was not exactly what I had pictured. Anna slept in a tiny bed with Mia at her side in a room lled with syringes, TPN kits, gauze, and tons of medication. The only vestiges of childhood were Mia’s favorite pink plastic horses lining a shelf, one of which her brother had bought her for Christmas, and some frilly dresses Anna had bought her. In the morning, Anna would bathe and dress Mia in a trying fashion. Mia’s muscle tone and rigidity forced Anna to get in the shower with Mia and hold her as she attempted to bathe her without Mia slipping out of her hands. Following these baths were the dreaded diaper changes. A regular and unnoticed occurrence for most children, diaper changes for Mia meant whole-body muscle spasms, screams of pain, and some- times seizures. I apprehensively watched her eke out a tiny smile as Anna dried her from her shower and kissed her cheeks, preparing her for the moment ahead. Then she would place Mia on her back and scramble for the wipes and diaper as Mia’s eyes rolled back, her hands ew up by her head, her body began to convulse, and a sound so disturbing it made one stop dead in one’s tracks erupted out of the child. As soon as the diaper was on, Anna would hold Mia to her chest, apologizing for her pain and plead- ing with her to stop. Mia would eventually calm down, her breathing slowing to a normal pace. Mia would then have her TPN infusion, and Anna would take Mathew to karate and Chinese school—all in a ‘normal’ day’s routine.

To this day, Mia has her good days and her bad days. Some days she will bless her family with her smiles, a small window into Mia’s soul, as if she has triumphed for a brief second over the mutiny inside her. She will enjoy stroller rides and listening to children’s television with her brother. She even enjoys “playing” Nintendo Wii against Mathew, as Anna slips the controller in Mia’s sleeve and wiggles her arm for her. On bad days, pain medication is not even strong enough to take the edge off, and spasms take hold of her body, leaving her in a deep sleep by day’s end and exhausting Anna. Bad spurts are further compli- cated by her erratic sleep schedule. In addition to losing many developmental milestones, she is gradually losing motor control of her extremities. She doesn’t make much noise at all anymore except for the repetitive grinding of her teeth, an outlet for her pain. Only an extremely at- tentive mother can tell when she is in pain and when it

is more than normal. Recently, this careful attention has amounted to catching a treatable small bacterial infection around the bottom of Mia’s central line that nevertheless required yet another hospitalization. Sadly, Mia’s parents have been told that the source of the bacteria was likely Mia’s gut, and that these infections will continue to happen again and again.

Mia today is an infant-sized two-and-a-half-year-old girl with slender extremities, graying hair, and a glazed stare. Despite this sobering image, I can’t help standing in awe of her strength as she endures hours of the same vision and physical therapy everyday. I watch as her mother fo- cuses every ounce of her attention on the simple rhythmic movements of her arms and legs and tells her how beautiful and strong she is for persevering. I can’t help laughing as her mom tickles her stomach, and Mia’s mouth opens as wide as possible, producing a huge grin. After therapy is over, Anna picks up Mia and holds her in her arms, and Mia turns her head up toward her mother, unable to see her but recognizing her touch. They face another day, difficult, but together.

What have I, as a future physician, learned from my experiences with Mia? Perhaps most importantly, as illustrated in some of the anecdotes above, pediatric chronic disease is not easily removed from its context. Mia’s entire family has been changed from this experience. Anna once related an experience in the grocery store, where she no- ticed people starting at her. One woman approached her and asked how old Mia was. Deciding whether or not to lie, she stated that Mia was six months old; however, the nosy bystander was not to be placated and asked her why the baby had so many teeth and so much hair. Annoyed and embarrassed, Anna raced through the check-out line and ran for the door.

Moreover, I have learned that when we do not have answers, it is then that we are particularly called upon to be more than just healers of the body. To this day, Mia does not have a diagnosis and has confused physi- cians repeatedly, yet each physician has affected the Mammens, having made some days easier than they could have been and some days more trying than necessary. Some physicians have dealt with Anna’s hysterics and anger directed towards them over lost blood samples or ignorant staff who have asked whether Mia drinks milk or exclaimed, “Your daugh- ter looks young for her age.” Those who sympathized eased Anna’s concern and earned her trust knowing someone else also had Mia’s best interests at heart. The leadership required to save a child’s life pales in comparison to the strength and leadership required of a physician when a child’s life cannot be saved.

Lastly, I see from Mia’s case precisely how much a patient can affect an individual. Mia may not talk or walk or ask cute questions, but, more than any child I have ever met, Mia has taught me a great deal. She has given me perspective on my own life and my hopes for my career in medicine. Every time I see her I can’t help being in awe of her ability to deal with the struggles of living in pain and ghting her disease and still managing to smile as if she were somehow comforting me. I start feeling that somehow this child is ahead of her time, knowing something I don’t—possibly some secret hidden meaning of life to which she is guiding me. Meeting Mia, for me, was like a wave to the sand, gone in a moment but leaving an imprint I will never forget. I remember now walking into the PALS Halloween party to meet Mia and Anna for the rst time and seeing this smiling bundle dressed up as Yoda. I was hoping I would help Mia in some way by being her PAL, but little did I know that she would do more for me than I could ever do for her.